Copyright: Ian D. Richardson Email: contact@preddonlee.com

First published in The Independent, London, April 28, 1997. Original article here.

A BBC foray into Arabic television ended in disaster a year ago [April 1996]. Ian Richardson on the fall-out from a sad and damaging episode in the corporation's historyToday [April 28, 1997], the BBC World Service announces that its widely acclaimed Arabic radio transmissions are shortly to be increased by five hours a day, providing the Middle East and North Africa with a continuous service of just under 18 hours a day. Ironically, this news coincides with the first anniversary of the closure of the ill-fated [original] BBC Arabic Television Channel.

Launched in June 1994, the channel was unique for several reasons, but primarily because it was funded by a Saudi Arabian conglomerate, Mawarid. The BBC's attempt to establish a Saudi-funded Arabic-language television channel beamed across the Middle East, North Africa and ultimately to Europe and the United States, was either brave or foolhardy - depending on your point of view.

The question - one that I have never been able to answer to my own total satisfaction - is this: was Mawarid's funding of the project also brave or foolhardy, or just naive?

The difficult negotiations for this channel had gone on between the BBC and Mawarid's subsidiary, the Rome-based Orbit Communications Corporation, for several months. World Service Television - as BBC Worldwide Television, the corporation's commercial arm, was then known - desperately needed a huge injection of funds to cover itself financially in the wake of Rupert Murdoch's surprise purchase of Star-TV, from which he had unceremoniously dumped the BBC's signal to the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and China. The idea of the Arabic channel was conceived, sold and purchased on the foundations and ethos of BBC World Service Radio's Arabic Service, which attracts a regular listenership of 14 million, making it arguably the most powerful media force in the Arab world.

World Service Television's chief executive, Chris Irwin, soon to fall victim to a classic BBC restructuring, had sought the views of his former World Service Radio colleagues at Bush House about the project. There were a number of senior people at Bush House who'd had bruising encounters with the Saudi Arabians, and they all urged great caution. There was particular scepticism about assurances from Irwin that Orbit was prepared to sign an agreement guaranteeing BBC editorial independence.

During the short life of BBC Arabic Television, there were several angry liaison meetings and phone

conversations with Orbit, and the guarantees of editorial independence proved to be a sour joke, only barely obscured by a thin smokescreen about the BBC's alleged failure to observe "cultural sensitivities" - Saudi code for anything not to the Royal Family's liking. It was only a matter of time before there would be a final parting of the ways.

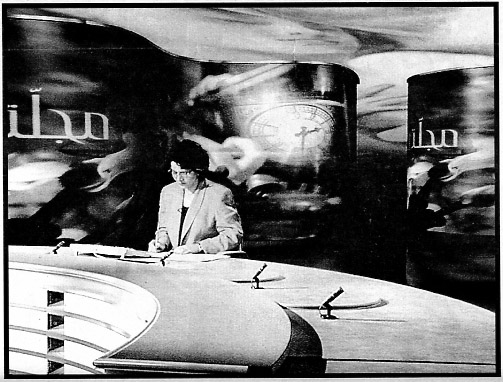

Orbit's agreement to work with the BBC for an "orderly wind-down" of the service proved to be worthless when Orbit simply switched off the BBC channel, at the close of transmissions on the night of Saturday, 20 April. The newsroom, the Arabic-language computer terminals, a purpose- built digital studio, the editing rooms and the presentation suites were all mothballed while Orbit exercised its ownership of the equipment.

Within days of Arabic Television being switched off by Orbit, several potential alternative backers had emerged and preliminary negotiations got under way in an atmosphere of great secrecy. These have come to nothing, and Worldwide has turned its attention to other partnerships.

There have been many losers from the Arabic Television project, not least the tens of millions of Arabs who have been deprived of the opportunity to have an unbiased, modern television service tailored to their own cultures and in their own language. And there's Orbit itself. Three years on from its launch, it is without the only channel that was both unique and prestigious, and its subscribers continue to be counted in thousands rather than millions.

The corporation's image in the Arab world was seriously tarnished by getting into bed with the Saudis to produce what some sections of the Arab press sneeringly called "the BBC's Petrodollar Channel". The abrupt closure provoked widespread jeers of "we told you so" and damaged the BBC's ability - and its will - to introduce multiple-foreign-language television channels, broadly emulating BBC World Service Radio.

It could be argued that it is no business of Britain to bother informing the rest of the world, but even Lady Thatcher took time off from her Beeb-bashing to praise and pump additional funds into the World Service, recognising the unquantifiable but undeniable spin-off for Britain from the corporation's global status. The additional benefit, as she would surely see it, was the fact that Arabic Television would have actually earned money for the BBC.

But there have been winners, not least the Middle East Broadcasting Centre (MBC), which transmits a free-to-air satellite service from Battersea in London to a huge audience across the Middle East, North Africa and a fair slab of Europe. It is owned by a branch of the Saudi Royal Family and it is, to say the least, a well-behaved operation when it comes to observing the Saudi view of media freedom.

But there has been another unexpected, more laudable, winner. While BBC Arabic Television itself may be dead, its editorial spirit, its style and even some of its programmes live on - transmitted from the tiny Gulf state of Qatar, which incidentally is also about to begin FM re-broadcasting of BBC Arabic Radio.

Al Jazeera (Island) Satellite Television went on air from Doha at the beginning of last Al Jazeera (Island) Satellite Television went on air from Doha at the beginning of last November, staffed chiefly by former members of BBC Arabic Television. While Al Jazeera Television's audience is still modest, its programme subjects are controversial, its interviewing techniques robust, and it is remarkably free of editorial interference.

The question yet to be answered is: will a wider success, or perhaps a political crisis in the Gulf, bring with it the need to trim its editorial sails? But then, who can say the same sort of question hasn't sometimes been asked of the BBC?

For more newspaper reports on this topic go HERE

BBC Arabic Television resumed broadcasting in March 2008 -- this time independent of any commercial partnerships. Ian Richardson, who was managing editor of the original service, left the BBC in August 1996 after 27 years with BBC World Service News and Current Affairs. He now owns Preddon Lee Limited and concentrates on book publishing and screenwriting.